Imaginary music (PRELIMINARY ENGLISH VERSION)

[home] <<summary <preceding

next>

[Français

![]() ]

]

The hunter of sounds, which we shall call more correctly " hunter of sound objects ", uses a microphone and a recorder. His purpose is not to record the whole flow of diverse sounds, but to constitute a sampling of chosen moments and elicitated sounds that are appropriate to his collection.

Two methods may be used :

the "angling fishing", consisting in putting himself in attitude of listening and observation, and in activating the recorder when something interesting happens ;

The " trawl fishing ", consisting in recording continuously the ambient sound environment, then in listening later to the recording to identify and sort out objects.

In both methods, live or recorded, the hunter has to put himself in attitude of attentive listening, rather by closing eyes, to recognize individuals in the multitude.

The exercise is easy when there is small multitude (or a lot of silence), but is not really interesting. Should the opposite occur, the hubbub can lead to a full discouragement.

For example the listening of the rumours of the city by being in the terrace of a cafe, besides the enjoyment inherent to the situation, brings many stimulations and profitable remarks to our comment. We thus encourage the reader to realize a try immediately, by inviting a friend to have a drink outside and to enumerate all the sound objects which he or she hears. It could give something as what follows.

" Hubbub of the traffic, conversations of the consumers, clatter of plates and glasses. "

Note: the traffic light switches to the green, and during several seconds the deafening noise of vehicles which start cover all the sound landscape.

" This is a group of engines which accelerate, among which I notice the characteristic music of a vintage Beetle. Let us wait they go away to distinguish other things. I hear now the percolator in the room behind, and then, next to us, a spoon which is moved in a cup. A moment of peace now: I even think I hear the far off sound of a bell, unless it should be a noise of pan in the back-room. But there is this person who bursts out laughing now in our right, and I can hear nothing else any more. "

Figure 1 : breaking wave

The sensations of sound intensity which we receive can vary from the almost inaudible level up to the deafening level. A sound object of strong intensity masks the others, and an object of weak intensity needs to be heard in a deep silence so that its presence may be discerned.

The exercise consisting in clearly distinguishing some sounds from the others is much more difficult from the analysis of a recorded tape than during the direct physical listening. Indeed, we benefit live from the ability of finding the positions of objects, and thus perceive the sound landscape in relief.

According to their left/right position, our pair of ears gets us a stereophonic listening, thanks to the light gap of time for the the sound to reach the two receivers distant from the thickness of our head.

When it is a question of characterizing a sound object as close or remote, it does not rely on the setting-up of ears. By experience, we associate the distance with sounds the colors of which lost some contrast during their spead out: weaker dynamics, fading of the high-pitched frequencies, the reverberation on walls.

During experiments of recording, below a certain level of volume, the tape recorder records nothing, otherwise a background noise if we raise the sensibility, and, on the contrary, over the level of saturation (the hand in the red), the recording is unintelligible.

The phenomenon is similar for the human perception, which is limited by a minimum and a maximum: the addition of the sound levels of all the objects must be superior at the threshold of perception (threshold of sensibility) and below the threshold of pain (threshold of saturation). Besides, as any human perception, that of the sound levels is not additive, but logarithmic: in the nineteenth century, two physiologists, Weber and Fechner, noticed empirically that the man is more sensitive to the relative difference between intensities than to the absolute values of the intensities. This perception of the differences of intensity is itself limited by the difference threshold. That is why the sound levels are expressed in decibels: to double the sensation of sound intensity it is necessary to multiply the acoustic excitement by 10, and the fact of doubling the acoustic excitement (for example to double the power of an amplifier) makes raise the perception only of three decibels (3 dB).

So practically ten cars produce only twice the noise of a single car, hundred chorus-singers sing only twice as loudly than ten chorus-singers and four times as loudly than a soloist. To be listened twice as loudly by the authorities, one thousand demonstrators have to go back ten thousand !

The ear has its maximum of sensibility in the frequency range of speaking, that is between 400 and 6000 Hz, and this sensibility depends on the frequency. Another physiologist, Fletcher, determined curves, named of isophony, by equal sensation of sound level according to the pitcht of the sound. For example, a very low sound of 35 Hz has to be 40 dB more energetic than a sound of 3 500 Hz to give the same sensation of intensity. These curves are established for an average population, but every individual can make establish his personal audiogram at his ear, nose and throat specialist doctor.

The physiological levels of intensity are measured in phones: zero phone corresponds to the perception threshold, 120 phones at the pain threshold. We shall understand, thanks to isophones curves of Fletcher (below), that the very low or very high-pitched sounds are easily blurred by the sounds of the human voice.

Figure 2 : Fletcher's curves

The hunters of sounds can testify of a hard law of the jungle in the world of the sound objects: the strongest crush the weakest. But, in the same way as, once the lion left, the zebras and the antelopes live peacefully in the vast meadows of Tanzania, which harmony can become established between simultaneous sound objects of comparable intensities?

In analogy with the world of the photo in black and white, we can make comparisons between the present sound objects thanks to parameters of light and contrasts: objects are small, the others rather big because they occupy many space. Some have precise outlines, the others are rather diffuse. Some are transparent or opaque, as they let or not hear the other sounds.

When there is harmony, that is that objects have close intensities, even numerous objects can be very clearly distinguished from the others, and this understanibility seems facilitated by the close / remote and the left / right spatial locations.

Several objects put together can or not mix in a single object according to the listeners or the circumstances. For example:

The conjunction of a cymbal strike and an chord hit on the piano is correctly identified by those who know well these instruments of the orchestra, while non-initiated will confuse the whole in a single instrument;

The noise of an engine in slow rotation contains a lot of information perceived by the expert ear of the mechanic. This sound object results from the combination of many others: the air admittance, the timing mechanism, pieces in rotation, the exhaust tube, etc... With the experience, the mechanic discriminates very well these very different sounds which evoke nothing else than a humming for the boeotian motorist (who maybe is besides an excellent musician).

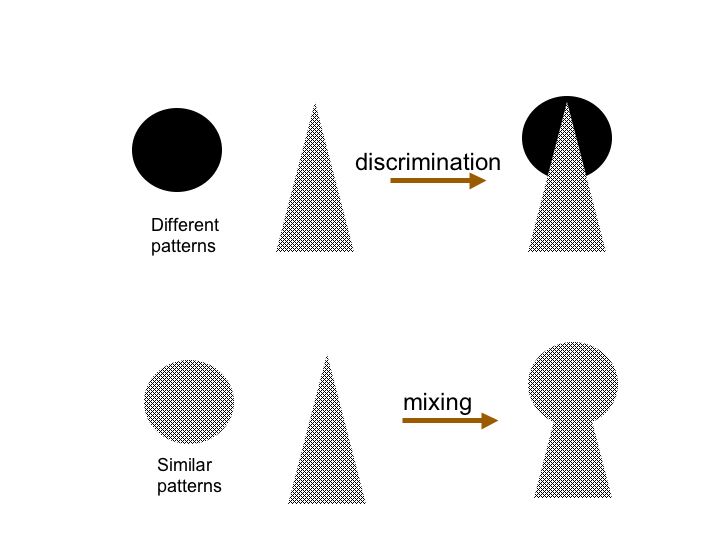

Figure 3 : mixing of objects

On the upper line, we stack a disk and a triangle filled with different patterns: the eye analyzes well the resultant image as a triangle and a disk. On the line below, both objects have the same pattern: the superimposing results naturally in a shape of lock hole for the one who would not have seen that it was a question about a triangle and a disk..

The auditive or musical experience is important for being able to discriminate between several simultaneous sound objects: as far as these sound objects are already well known, the discrimination is easy. If they are not well known, the confusion is almost systematic. For example, the mixture of two sounds of synthesizer not having been previously understood separately: they are merged by the listener as forming a single object; what can moreover be the searched effect.

Paradoxically it can be a stake for the conductor of a symphony orchestra to make the orchestra sound as a single instrument with a new and rich tone, what amazes the most educated listeners. This is playable for the symphonic music, because the variety of instruments is limited and is a part of the culture. On the other hand, for the electronic music, the sound objects are "unheard", and thus very miscible in the ear of the listeners to create other original objects. An option for the composer, before playing combinations of objects, would be to expose at first separately these objects so that the liteners know how to identify them.

The considerations above help us to distinguish some tangible characteristics to describe the result of the listening of the presence of the sound objects. These characteristics are individual or relative to the other presents objects :

Audible / unaudible :

masked or not by another object ;

Strong / weak :

level of felt sound intensity ;

Dominant / equal / dominated :

position with regard to the others ;

Ponctual / distributed :

in stereo, as the acoustic source appears as punctual (ex: a singer) or massive (ex: a choir).

Close / remote :

the ear perceives as remote a sound the color of which is not contrasted: weak dynamics and lowering of high-pitched frequencies; we shall see farther that this effect is emphasised by the reverberation.

Imaginary music ISBN 978-2-9530118-0-7 copyright Charles-Edouard Platel

[home] <<summary <preceding top^ next>