Imaginary music (PRELIMINARY ENGLISH VERSION)

[home] <<summary <preceding

next>

[Français

![]() ]

]

Figure 1 :

to discover a musical work is like to discover an

island …

(Tagomago, Baleares)

Figure 2 :

…or visit a territory

(a farm in the Hurepoix country)

An interesting experiment would be to verify if a listener has the same evaluation of the duration of a piece of music, for example the fifth symphony of Beethoven, in two different situations: in playing the disk and in concert. The objective answer would be that the time of the concert dedicated to this work, which includes the end of the interlude, the moment put by the orchestra to tune the instruments, the performance of the work, the salute of the conductor, and the applauses at the end, is certainly longer.

However, either in a concert hall or in a living-room, the listener identifies the same thing as an intended art object: this includes all the sounds perceived during the interval between the silence of the beginning and the silence of the end. It is a very dissociable and significant moment with regard to an usual or commonplace sound environment.

In the same way, our glance distinguishes the painting or the photo from the wall where it is hung on, or the building from the landscape. The listening is a deliberate attitude.

|

In 1954, John Cage created a work called " 4 minutes 33 seconds ", during which a pianist remains silently arms folded in front of his instrument, without playing a single note. When this paradoxical and surprising work is in the program of a concert, the public puts himself in an attitude of intense listening during the 4 minutes 33, which often are concluded by enthusiastic applauses. The success of this experiment depends effectively on our intention of listening and on that of the other participants. |

By looking closer at the piece of music in its duration dimension, several parts may exist, which are separated by silences.

Mostly every part is characterized by an "atmosphere", which comes from the used sound palette, or from the type of playing (piano, forte), and by a "stress", which arises for example from the frequency and from the variety of the events or from the surprises.

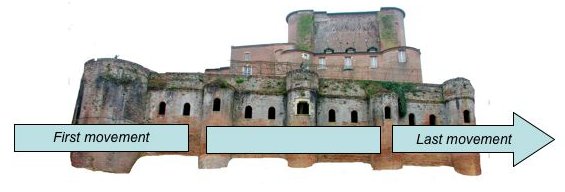

The first and last movements have a particular role: they allow to enter the work, then to go out of it; this confers them the role of door to access inside, then to exit towards the outside. So, at the beginning, the listener enters, or stays aside. The last movement provides the exit to the few seconds of silence which precede the return to the everyday life.

Figure 2 : evocation of contours of a musical work

Here are two ways to return the listeners into the everyday life :

when the music stops simply and without preparations, what gives a feeling of abrupt awakening after a dream; the souvenir remains clear; maybe there is frustration (or easiness!) ;

when the piece ends without ambiguity with its final movement, (examples in romantic period with a lot of brass instruments and percussions). It feels rather like a "sleeping on " awakening ; the souvenir which will stay is explicitly imposed by the composer; the listener knows that he approaches the end of the piece, and he savors the dessert, a sweetened syrup on the big pastry.

The intermediate movements constitute the internal domain of the work. They are like the various rooms of the visit of the castle, with possible entrance and exit gates.

Up to this point, we considered the duration of a work on a global plan. Now let us look at this duration with a magnifying glass, because inside the duration of a piece of music there is a big succession of sounds, sometimes very quickly.

Definitely, have we a precise notion of what is a sound?

In musician's classic terms, a sound is characterized by its pitch, its tone and its duration ;

In terms of acoustics, a signal, sound or noise, is characterized by its frequency spectre, the shape of its envelope, and its duration.

Do we speak about sound or about noise? For the acoustician, the sound is a particular noise, and for any open-minded musician, any noise can be an interesting sound.

A sound or a noise is described in a common way by speaking about its natural or instrumental characteristics: percussions, sustain, reverberation, echo, vibrato, tremolo, low or high pitched, brilliant, thud, etc., either in reference to the object or instrument which emits the sound: violin, trumpet, bell, rain, plane, pebbles, voice, thunder, bird...

The descriptive possibilities depend on our collection of analogies, archetypes and cultural marks: so the expression " a sound of bass " does not evoke the same matter for a classic musician or a jazzman.

With the magnifying glass (or rather with an attentive ear), let us deepen the observation of sounds placed in the duration dimension: how to identify or track down sound objects, that is, elementary, locatable and recognizable sounds as such.

We shall agree that a sound object is the shortest object that can be listened, that is, both individually audible and recognizable along the progress of the duration.

The sound object is a molecule or a grain of music. The linguists use for their domain the concept of phoneme.

Then, having isolated such or such sound object, we try to describe its own specificities.

We can refine again by observing sounds in the electron microscope, or just stay there in order to approach the question by the other angles later.

By the acoustic analysis, every molecule may be chemically cut in more elementary atoms. Making it, as in the chemistry, the specific properties of the molecule which we "broke" are left aside, because with the same atoms combined differently we can synthetize a big variety of other molecules having very different properties. The exploitation of this way provides a very rich mine for the modelling of synthesizers, but cannot be achieved by most listeners in situation of listening.

The listener, having only his own auditive faculties to analyze, will be rather sensitive to the perceptible nuances of duration and of the two other constituents: color and presence, which we shall develop in the following chapters.

|

The concept of " musical object " was introduced by Pierre SCHAEFFER in his book " the Musical Objects Treaty ". He gaves a richer definition than our trivial sound object, because SCHAEFFER considers that the musical object has to offer a musical interest. So our route crosses here that of the "Treaty" while following a different path; but farther we shall find other crossroads. |

Figure 3 : taking flight (Parc du Teich, Gironde)

It would seem disproportionate to analyze every piece of music sound object by sound object. So much to admire a beach grain of sand by grain of sand or pebble by pebble, or a waterfall drop by drop.

Also, if we analyze a rhythm of percussions, it is boring and rarely useful to analyze individually every hit on the skin of the instrument. Really, it is the recognizable sequence of repeated appearances of the same sound object or of similar objects that interests us. It is also true for a melody sung or executed by an instrument, for a chirping, for gurglings, etc.

The occurrences can be random (as raindrops) or regular (as a footstep noise). We rigourously identify a set of objects, but we pay our attention to the whole group of sounds. We can consider that the sound groups are as "granular" objects, and that all the interesting properties of the sound objects can thus apply to the sound groups.

Figure 4 : appearance

Let us start from an example: a blow of cymbal is a sound object which lasts about five seconds. A chord of guitar can last approximately the same time. An interesting fact is that the sounds of cymbal and guitar have very different pitches and tones. But another interesting fact is that they have a common duration of five seconds.

For the listener, before the blow of cymbal, or before the chord of guitar, that is before the appearance of the object, this object is absent in the sound space, and when the sound vanishes at the end of the about five seconds, the object seems to go out of the sound space. Thus, something is here able to arouse the interest of a listener in attitude of listening. This thing is the creation of sound events:

appearance : the absent or non-existent object becomes present in the sound space ;

disappearance : the present object becomes absent in the sound space.

Any sound object causes at least the two sound events identified above. This trivial but indisputable remark leads to a suite of consequences which will feed our thoughts. Here is a first consequence :

If an object appears for the first time, it causes a particular event: during this first appearance, the listener can memorize it and remember it later. For this listener, the object acquires a status of existence in his memory, even when it will disappear from the sound space.

When we hear a melody or a particular sound object, this can evoke us an air, a sound or a known noise, or evoke nothing at all. We thus qualify the event in a different way if we can or not identify and recognize this object.

To recognize it, we need to have heard it previously, at least once, and we need that at this time this sound object impressed our memory. Our memory contains many musics and familiar noises. If a sound object causes to evoke one of these, we cannot be indifferent to it.

Conversely, during its first appearance in the sound space, an object can evoke nothing in the memory of the listener; however, its original character can, at this moment, awaken the interest, and activate a memorization which can be evoked again later.

In summary, the character of indifference or interest depends on the sound object itself, on the personality and the culture of the listener, and also the more or less favorable conditions of listening.

The appearance of a sound object, which is an objective event, thus causes a subjective impact differing according to the recognition and the interest felt by such or such listener.

According to this impact, the listener can give qualifiers to the sound object which has just appeared:

absent / present ;

unknown / known;

indifferent / interesting.

It is only when the object is present (audible) in the sound space that the listener can be concerned by it. In illustration, the doctor practising tests of audition asks to his patient to declare with objectivity if he hears or not neutral sounds which do not affect the subjectivity of most people.

How the listener is or not able to identify it.

It can be known by the listener before the first appearance, because culturally familiar (natural sounds, musical instrument).

He can still be unknown in spite of the first appearance if, due to the lack of interest, there was no memorization by the listener.

Consciously or unconsciously, such or such listener will judge that the presence of such or such sound object provides an interest.

Is the listener able to be captivated by the sound objects? By which process?

To understand it, we shall need to analyze also the effects on the listener of the other constituents of the object, that is the color and the presence.

At this point of our investigation, we have just brought to light that the listener is attracted by the suite of the sound events which mark out his perception of duration. But the environment of the listener is not only sound. Other rhythms stimulate him, like his conscious movements and gestures or his own biorhythms. These rhythms can be coupled to those suggested by the suite of events of the music.

The composer can play with a loose coupling (as for a background noise) or a tight coupling (as for a military march). He can play with couplings and uncouplings, oppositions and conjunctions of beats ; he can let the heart rhythm to take the respiratory, try the resonance with the alpha waves, etc..

The tempo is not mechanical. Except voluntary effect, the time of the chronometer or the metronome is not felt by the listener. He perceives intervals of duration between events concerning sound objects.

At a given moment, the smallest perceptible duration interval is the time which separates two sound events such as we defined them, bound to different objects or to the same object. This measure is thus variable during the progress of the work, as if the time was graduated in a elastic way.

So, in the world of the music, when we shall say " at the given moment ", this moment can be worth a tenth of second (by ex: a finger snap) as well as one hour (by ex: some minimalist works of La Monte Young can suggest the eternity of a single moment).

When the music is associated with a spectacle (dance, theater, cinema, fireworks, lighting effect), the sound and visual events overlap in the duration, and articulate to create the rhythm of the whole spectacle.

Figure 5 : July 17th, 2006 at 20 UTC

Imaginary music ISBN 978-2-9530118-0-7 copyright Charles-Edouard Platel

[home] <<summary <preceding top^ next>